Disaster Mitigation: Preparing a Health Care Facility for a Water Crisis

When a hospital’s water supply is compromised, patient care is jeopardized.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, Baptist Hospitals of Southeast Texas was confronted with a staggering reality. Though the Beaumont, Texas medical facility was thoroughly prepared for the Category 4 hurricane, the city was not. Both of Beaumont’s water pumps had failed.

“We have staff here. We have food and supplies here. We were ready to rock and roll,” said Mary Poole, the hospital’s director of public relations in an interview with CNN. “Unfortunately, the city is not cooperating with the water.”

Hospital leaders were faced with a difficult decision: to ship in water and hope that the city’s infrastructure would be rapidly repaired or to move 193 of the city’s most vulnerable people to cities far from their friends and families.

Ultimately, the hospital administrators decided it was too risky to stay, and the patients, including infants from the neonatal intensive care unit, were airlifted to hospitals in Dallas, Galveston and even as far as Missouri.

In January of 2018, a New Hampshire hospital lost access to running water as a result of water damage from flooding, forcing the postponement of all elective surgeries. In July of this year, a New York hospital had to lean on bottled water and packaged bath wipes after officials found the presence of Legionella bacteria in the hospital’s water supply.

A community’s health and welfare depend on its medical facilities, and medical facilities rely on their water capabilities to provide patient care services. Unfortunately, water systems are fragile and vulnerable to a multiplicity of threats, including natural disasters, infrastructure failures, and biological hazards. When a hospital’s water supply is compromised, the safety of patients, the quality of care, and daily operations are all impacted.

A community is only as resilient as its health care facilities.

While most medical facilities have invested in large generators for power in the wake of disasters, few have redundancies set up for water in the case of interruptions to their normal supply. In their report on emergency water supplies for hospitals and health care facilities, the CDC and the American Water Works Association recommend the development and implementation of an Emergency Water Supply Plan (EWSP) to prepare for, respond to, and recover from a compromised water supply. A comprehensive EWSP should take into consideration several factors, including capacity, autonomy, and redundancy.

Capacity

Each Emergency Water Supply Plan will be different from every other based on the unique needs of the medical facility in question. Large, urban health care facilities will have different needs from a small, rural hospitals. In the development of an EWSP, a medical facility must create an accurate portrait of its capacity in the event of a disaster. This includes an assessment of repair capabilities and facility schematics, an audit of water usage, and an analysis of viable emergency water supply alternatives.

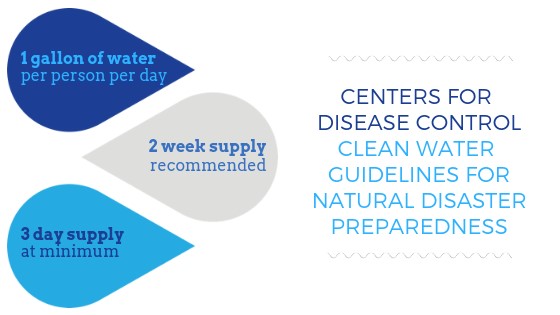

During a natural disaster, a healthy person will require at least one gallon of water daily, according to the CDC. The guideline is higher in warmer weather, and also increased for those who are pregnant or sick. At minimum, the CDC recommends storing three days’ worth of water per person, though having a two week supply ready is ideal. For a hospital with patients who require more water usage for dialysis and other treatments, more will be necessary.

Autonomy

Many businesses rely on the national guard to come in with loads of bottled water, but in rural areas especially, that may be days or even weeks. While bottled water and wet wipes may suffice for a short interruption to a limited area of a hospital, a resilient facility is one equipped to generate its own water supply.

Autonomy relies on a well-developed and rehearsed EWSP, the coordination of institutional knowledge, and the augmentation of internal repair capabilities. Additionally, hospitals with a supplemental water source and built-in water supply redundancies will be better prepared than those without.

Redundancy

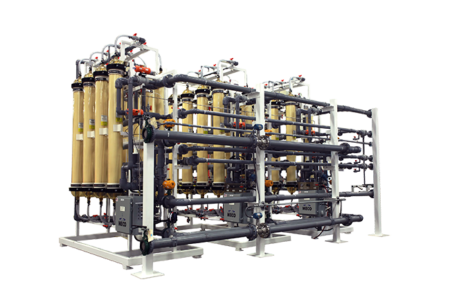

In each of the cases of interruption cited earlier, redundancy could have prevented the closures of the facilities. A water purification system is perhaps the most efficient means of building redundancy into a hospital’s water supply. Reverse osmosis systems provide an expedient source of clean water to those who need it most.

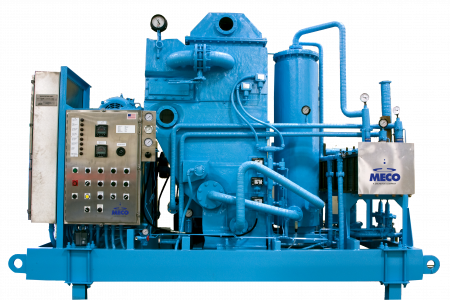

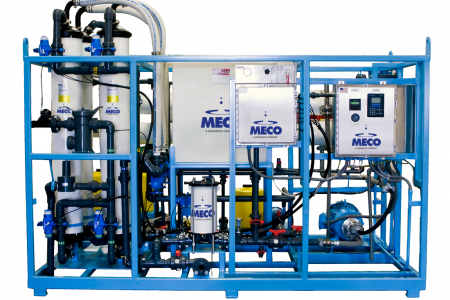

MECO’s MMRO-LT system is an industry standard for desalination, which turns salty or polluted water into potable water. Because spare parts are readily available, it’s fast and easy to repair the MMRO-LT and prepare it for high-demand times such as disasters. System designs are customizable, allowing medical facilities to create a system that meets their capacity requirements in gallons or cubic meters per day.

To determine the system you will need, consider the maximum number of people in your hospital who will need clean water under the worst conditions as well as the medical procedures and daily operations that require clean water. For instance, a Gulf Coast hospital with a capacity of 200 patients and 100 personnel would need to imagine water needs during the height of hurricane season when temperatures and hydration needs often skyrocket.

Contact MECO for industry-leading disaster relief water purification.

MECO manufactures state-of-the-art reverse osmosis systems ideal for disaster relief. Our systems lead the industry in terms of output, efficiency, longevity, and lack of maintenance. Whether you’re preparing for emergency disaster relief for a community or a hospital, MECO offers the best water purification systems on the market.

Contact MECO today for questions about innovative and efficient water purification solutions for your medical facilities.